Lasiurus borealis - Red Bat

The

Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals edited by D.E. Wilson and S. Ruff.

1999. <http://www.discoverlife.org>.

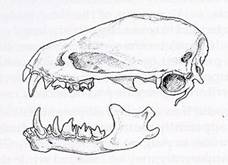

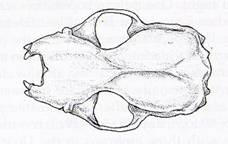

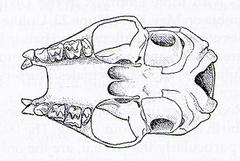

Skull Pictures:

*Left lateral

view of skull and mandible

<http://www.discoverlife.org>.

1998. The

Mammals of Virginia by D.W. Linzey.

*Dorsal view

of skull.

<http://www.discoverlife.org>.

1998. The Mammals of Virginia by D.W. Linzey.

*Ventral view

of skull.

<http://www.discoverlife.org>.

1998. The Mammals of Virginia by D.W. Linzey.

Physical Description:

Adult total length: 3 5/8th - 4 7/8th in. (92 - 122mm)

Tail: 1 ½ - 2 ½ in. (38 – 63mm)

Hind foot: 3/8th in. (8.5 – 10mm)

Weight: 1/5th – 3/5th oz. (6 – 14g) (http://www.discoverlife.org)

Bats, are unique mammals due to many characteristics: usage of both legs and wings during flight, elongated fingers to provide wing membrane support, keeled sternums for enlarged flight muscle attachment, partially fused vertebrae, forelimbs specialized for true flight, and flight membranes that are extensions of the back and belly and connect the body with the wings, legs, and tail.

Lasiurus borealis, The Eastern Red Bat’s fur contrasts significantly in color between the sexes. Male fur is generally bright red-orange or brick red to rusty red with a narrow band of red below and a larger band of yellow below that. Guard hairs are generally white tipped producing a slight frosted effect. Females are a dull buff-chestnut color with white frosting. Both males and females have a yellowish-white patch on the front of each shoulder. The membrane extending from the tail to the hind legs is known as the interfemoral membrane. The dorsal surface of this membrane is thickly furred. The ears are short, broad, and rounded and when laid forward reach slightly more than halfway from the angle of the mouth to the nostrils. The basal two-thirds of the ears are densely furred. A completely furred uropatagium with the Patagium black and furred from body and elbow and along forearm is exhibited. The wings are long and narrow with general wingspan measurements between 11 to13 inches in width. Short, rounded, ears are visible and white markings are visible on shoulders and wrists (BATCOW, Tuttle 2002).

Smithsonian

Book of North American Mammals edited by D.E. Wilson and S.Ruff. 1999. <http://www.discoverlife.org>.

The species’ mottled red coat protects it by giving the bat an appearance similar to a dead leaf. This works as camouflage and accounts of Lasiurus borealis have been found hibernating on the ground in piles of leaf litter. They also hang from tree branches or tree leaf petioles which can camouflage them as rotting fruit. They often prefer peach trees (BATCOW, Tuttle 2002).

Economic Importance for Humans:

Positive Aspects-

Red bats almost never enter human habitation. It is rare to find Lasiurus borealis invading anthropogenic residential homes. They aid in keeping various insect populations (particularly mosquitoes) low (BATCOW, Tuttle 2002).

Negative Aspects-

Some humans view Lasiurus borealis and other bat species as threats. Humans should be aware that bats are capable of transmitting two diseases to humans – Rabies (causative agent a Rhabdovirus) and Histoplasmosis. Histoplasmosis is a disease caused by inhaling dust that contains contaminated spores. It is stated: "less than a half of 1 percent of bats contract rabies, a frequency no higher than that seen in many other animals. Like others, they die quickly, but unlike even dogs and cats, rabid bats seldom become aggressive." A misnomer is that bats attack when they get rabies, this is false as they are stagnant and reside, unmoving, in one place. It is rare for humans to contract rabies from infected bats. People handling bats should be aware of this possibility and take necessary precautions (Tuttle, 1988, http://biology.usgs.gov, http://www.discoverlife.org, Fenton and Becht 2002).

Tuttle

(BCI)

Conservation:

The heritage status of Lasiurus borealis is “G5: Secure-Common, widespread, and abundant (although it may be rare in parts of its range, particularly on the periphery). Not vulnerable in most of its range, and with considerably more than 100 occurrences and more than 10,000 individuals.”

-IUCN Category: This species has not been evaluated or is considered of Lesser Concern by the IUCN.

-CITES Status: Not currently listed by CITES

(www.natureserve.org, Wilson and Reeder 1993, Reed 1997, Hall 1992).

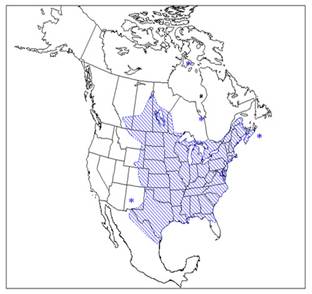

*= isolated or

questionable records

http://www.batcon.org/discover/species/lboreal.html

L. borealis occur throughout much of eastern North America, generally east of the Continental Divide from southern Canada south to northeastern Mexico (Baker et al. 1988; Hall 1981; Ramirez-Pulido and Castro Campillo 1994). Winter causes the range to occur throughout the southeastern U.S. and northeastern Mexico with concentrations highest in coastal Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico regions. Females generally occur in more southern areas. Males tend to be more common in northern areas during winter (Davis and Lidicker 1955; LaVal and LaVal 1979; Padgett and Rose 1991).

Geographic Range:

Lasiurus borealis is distributed throughout all of Wisconsin and from northern Mexico and the eastern and central United States to southern Canada. Its range extends westward to southwestern New Mexico, eastern Colorado, western North Dakota, and southwestern Alberta.

North America Range Map http://www.discoverlife.org

It is also a native of the Bahamas, Cuba, Dominican Rep., Haiti, Jamaica, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Trinidad/Tobago (www.discoverlife.org, Linzey and Brecht 2002, http://www.natureserve.org, Wilson and Reeder 1993, Reed 1997, Hall 1992).

Overview Map (www.natureserve.org)

Note: indicates

countries of occurrence, actual area occupied by the species is usually much

less.

Ontogeny and

Reproduction:

Observations suggest that the sexes migrate separately in the spring and occupy different summer and winter ranges in some areas. Mothers frequently give birth to twins and triplets (BCI, Tuttle 2002).

© Merlin D.

Tuttle, Bat Conservation International

www.batcon.org

With the exception of mothers and their offspring, red bats and other bats of the genus Lasiurus generally roost solitarily. The mother in this picture is nursing quadruplets while clinging to a grapevine. Unlike most other bats, red bats can have more than one pup (BCI, Tuttle 2002).

The mother in

this picture is nursing quadruplets while clinging to a grapevine.

(BCI).

Eastern red bats usually mate in August and September, although the park mammal collection contains two red bats in copulation that were taken on April 5. Females store sperm in their reproductive tracts during the winter and ovulate in early spring. Following a gestation period of 80-90 days, 1-5 young are born in June. The lasiurine bats, particularly the red bat, are the only bats known that normally have 3 or 4 young per litter. At birth the young weigh about 0.5 g each, and by 4 weeks of age they weigh nearly half of the mother's weight. Between 3-6 weeks of age they can fly and are ready to be weaned between 4-6 weeks of age (http://www.discoverlife.org, Linzey and Brecht 2002).

Ecology and Behavior:

The senses of sight and hearing are well developed in Lasiurus borealis, and bats in general. Most bats become active near dusk and are active much of the night so sight is of little importance in navigation and in the capture of prey. Via echolocation they emit ultrasonic calls far above the range of human hearing that are reflected from objects ahead of them. They hear the echoes and are able to avoid obstacles and find food in total darkness. Different species can be distinguished by differences in the structure of their echolocation calls (http://www.discoverlife.org and Fenton and Bell, 1981).

© Merlin D.

Tuttle, Bat Conservation International

BCI

During feeding maneuvers, the tail and wing membranes are used to capture and restrain prey. Some insects are captured by the tail membrane, which forms a pouch-like compartment. The bat must bend its head forward in order to grasp the insect with its teeth and take it into its mouth. Sometimes the bat may use its mouth to capture an insect from its wing. Groups of several bats forage and interacts near street lights (Hickey and Fenton, 1990), where they feed on an abundance of insects especially Lepidoptera (Acharya and Fenton, 1992 and http://www.discoverlife.org).

Lasiurus borealis have been found to eavesdrop on conspecifics (Balcombe and Fenton, 1998). This often leads to chases between bats (Hickey and Fenton, 1990), in which low-frequency vocal interactions are common (M.K. Obrist, personal observation). This suggests that lower-frequency bands are used in communication. Red bats use a long, final, narrow-band component in sonar signals when foraging over long distances (Obrist, 1995), but the dominant search-call frequency does not seem to be tuned in to their outer ears (Obrist et al 1993) (Obrist and Wenstrup 1997).

During colder times Red bats roost in the foliage of deciduous trees and are seldom found far from forests. During the day they suspend by one foot and wrapped in their big furry tails they look similar to dead leaves. They come together only to mate and migrate and live solitary lives. One of the largest bat hibernacula in the Upper Midwest occurs at the Neda Mine State Natural Area (WDNR, 1989), near the southern end of the Niagara Escarpment in Wisconsin. The caves, sinkhole features, and excavations associated with the former mine, provide summer roosting and winter hibernating sites for significant numbers of bats. Other areas of the Escarpment, e.g., at Door County’s Peninsula State Park, are also known to harbor bats but the regional and local significance of these sites is unclear (http://www.discoverlife.org).

Hibernation sites are usually tree hollows or under leaf litter. Unlike most other hibernating bats, red bats often arouse and feed, even in January if temperatures rise above 55 F. At such times, they can be seen feeding in bright sunlight as early as 2 or 3 in the afternoon. During the coldest weather, red bats have the ability to raise their metabolic rates enough to ensure a body temperature above their critical lower survival limit of 23 F. When winter temperatures rise above 55 F they arouse and feed, often in the brief warmth of mid-afternoon, in order to capture the few available insects (BATCOW, Tuttle 2002, BCI).

Habitat:

Lasiurus borealis are often found along forest edges, edge habitats in general, or around street lamps, where they hunt for insects, especially moths. Sometimes, they congregate in large numbers around corncribs where they feed on grain moths associated with such. Predators on red bats include several birds, especially blue jays. Lasiurus species are commonly referred to as tree bats due to their general roosting in the foliage or trunks of trees (Griffin 1970,BCI, Tuttle 2002).

Remarks:

The Spanish common name of Lasiurus borealis is “Un Murciélago” (www.natureserve.org)

John Ragan of Troy, Michigan, has documented the first red bat to use a bat house. He also attracted 245 little brown bats to seven of 12 houses on poles and a wooden building. The red bat used just one location in the middle crevice of a medium-sized house painted black and mounted on the building. The red bat stayed for one night only in July 1996 and again in July 1997. This solitary species normally roosts in tree foliage, and this is the first observation of one from a crevice, much less a bat house. Ragan will report next year if the red bat returns. Ragan’s other successes attracted the attention of several raccoons, who preyed on about 10 to 15 bats in his pole-mounted houses. He thwarted their efforts by installing metal predator guards around the base of each pole. The raccoons did not give up easily, leaving claw marks in the metal, but were unable to capture any more bats (BCI).

In the submandibular gland of Lasiurus borealis “striated duct cells lack granules and instead have an array of rod-like structures oriented perpendicular to the apical plasma membrane to which they appear to be attached by very short filaments” (Tandler and Phillips, 2000).

Literature Cited:

Acharya, L. and M.B. Fenton. 1992. Echolocation behaviour of vespertilionid bats (Lasiurus cinereus and Lasiurus borealis) attacking airborne targets including arctid moths. Canadian Journal of Zoology (70): 1292-1298.

Bat Conservation of Wisconsin Inc. (BATCOW) in association w/ Merlin D. Tuttle. 2002. <http://www.batcow.org>.

Baker, R. J., J.C. Patton, H.H. Genoways, and J.W. Bickham. 1988. Genic studies of Lasiurus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae). Occasional Papers, The Museum, Texas Tech University 117: 1-15.

Balcombe, J. and M.B. Fenton. 1998. Eavesdropping by bats: the influence of echolocation call design and foraging strategies. Ethology 79: 158-166.

Bat Conservation International (BCI) in association w/ Merlin D. Tuttle. <http://www.batcon.org>.

Carroll, S.K., T.C. Carter, and G.A. Feldhamer. 2002. Placement of Nets for Bats: Effects on Perceived Fauna.” Southeastern Naturalist 1(2): 193-198.

Cryan, P.M. 2003. “Seasonal Distribution of Migratory Tree Bats (Lasiurus and Lasionycteris) in North America.” Journal of Mammalogy 84(2): 579-593.

Davis, W.H., and W.Z. Lidicker, Jr. 1956. “Winter range of the red bat, Lasiurus borealis. Journal of Mammalogy 37: 280-281.

Linzey, D.W. and C. Brecht. 2002. <<http://www.discoverlife.org>.

Fenton, M.B., and G.P. Bell. 1981. Recognition of insectivorous bats by their echolocation calls. Journal of Mammalogy 62 (2): 233-243.

Griffin, D.R. 1970. Migration and homing of bats. Biology of bats (W.A. Wimsatt, ed.): 233-264. Academic Press, New York.

Hall ER. 1982. The Mammals of North America 1 and 2. Mammalian Species, nos. 1-604. Published by the American Society of Mammalogists.

Hickey, M.C. and M.B. Fenton. 1990. Foraging by red bats (Lasiurus borealis) do intraspecific chases mean territoriality? Canadian Journal of Zoology 68: 2477-2482.

LaVal, R.K., and M.L. LaVal. 1979. Notes on reproduction, behavior, and abundance of the red bat, Lasiurus borealis. Journal of Mammalogy 60: 209-212.

Mager, K.J. and T.A. Nelson. 2000. Roost-site Selection by Eastern Red Bats (Lasiurus borealis). The American Midland Naturalist 145(1): 120-126. <www.bioone.org/bioone/?request=get-document&issn=0000031&volume=145&issue=01 &page=0120>.

Obrist, M.K., M.B. Fenton, J.L. Eger and P.A. Schlegel. 1993. What ears do for bats: a comparative study of pinna sound pressure transformation in Chiroptera. Journal of Experimental Biology 180: 119-152.

Obrist, M.K. 1995. Flexible bat echolocation: the influence of individual, habitat and conspecifics on sonar signal design. Behavioral Ecol. Sociobiology 36: 207-219.

Obrist, M.K. and J.J. Wenstrup. 1998. Hearing and Hunting in Red Bats (Lasiurus borealis, Vespertillionidae): Audiogram and Ear Properties. Journal of Experimental Biology 201: 143-154.

Padgett, T.M., and R.K. Rose. 1991. Bats (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) or the Great Dismal Swamp of Virginia and North Carolina. Brimleyana 17: 17-25.

Ramirez-Pulido, J. and A. Castro-Campillo. 1994. Bibliografía reciente de los mamiferos de Mexico 1989-1993. Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana, Mexico City, Mexico.

Reid, F. A. 1997. A field guide to the mammals of Central America and southern Mexico. New York, Oxford Univ. Press.

Tandler, B, and C.J. Phillips. 2000. Organic Secretion by Striated Ducts. European Journal of Morphology 38 (4): 233-236.

Tuttle, M.D. 2000. A Decade of Bat Conservation 10 (1): 3-10. <http://www.batcon.org/batsmag/v10n1-1.html>. Last updated 1997.

Wilson D.E. and D.M. Reeder. 1993. Mammal Species of the World, a Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Second Edition. ashington, Smithsonian Institution Press.

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). <www.dnr.state.wi.us/org/land/er/publications/niagara/Results.asp>.

Reference written by Nicole Woodward, Biology 378 student. Edited by Christopher Yahnke and Jen Callahan. Page last updated 4-27-04.